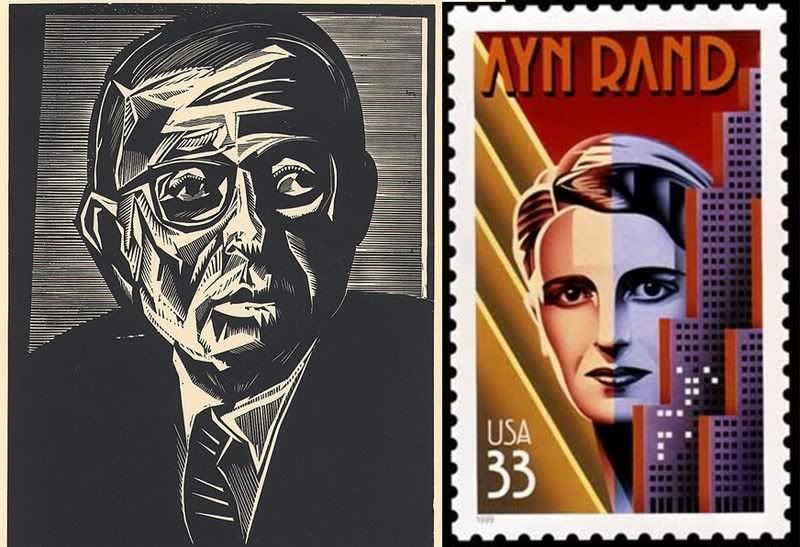

Sartre and Ayn Rand Would Have Had Some Weird Children

I am planning a slightly more involved post on Sartre for tomorrow, but I wanted to preface it with a question that has plagued me for some time. Are Sartre and Ayn Rand just cultural variations on a theme?

As a disclaimer, let me point out that I think Sartre’s nifty. Also, reading Sartre was one of the factors that pushed me from being interested in philosophy to wanting to study it professionally (I know I shouldn’t admit things like this publicly, but in my defense: I was 16 at the time). And I still think that, in many ways, Being and Nothingness is a genuinely great work of philosophy: it was one of the very few major works that aimed not just at resolving abstract metaphysical problems, but very sharply followed that ancient dictum of philosophy: Know Thyself. Sartre’s account of self-deception and the numerous permutations of it worked out throughout the book serve me well to this day in analyzing both myself and other people.

My feelings for Ayn Rand are a bit less warm. I read The Fountainhead when I was 17 (in order to enter the essay contest) and tried to follow up by reading some of her theoretical work; fortunately, I’d already read enough real philosophy by then to find her pretty laughable. I still think The Fountainhead is, overall, a good novel despite being seriously undermined by the attempts to get a “message” across (though Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith is a more realistic and overall superior attempt at something similar: for one thing, it’s peopled by real characters rather than thinly disguised social virtues and vices). But really, I pretty much think Rand is a joke. Sartre, on the other hand, isn’t. And his tireless political commitment, though occasionally misguided, is impressive. So, what’s the connection?

What they share, really, is a similar delusion, or perhaps a similar lie: that they are conveying an uncomfortable truth when, in fact, they are telling the people exactly what the people want to hear. Let’s look at Rand’s case. The harsh truths she tells her American audience go something like this: Capitalism is wonderful. The world is objectively real. The highest value is individuality. Individuality consists of never collaborating with others, as that would water down the uniqueness of this individuality. And, naturally, morality requires that we care only about our own happiness and self-interest. Yup, integrity means looking out for number one. Obviously this is earth-shattering stuff.

Sartre is a better writer (though he also has a tendency to undermine the plausibility and readability of his fiction by overly un-subtle philosophical messages), and a much better philosopher, but this is to be expected: the French public is simply more demanding of its intellectuals. But what seems a bit disingenuous are his remarks about the “dreadful burden” of our freedom. He is telling a public that has just emerged from an occupation (in which many were complicit), a public that no longer trusts the old values, that, hey, it’s ok: the old values are only right if you choose them. And you’ve got the power to break free. All you have to do is recognize it! Sure, Sartre was accused of corrupting the youth and preaching despair, and I suppose his philosophy would’ve been more troubling if he were not preaching to the choir. But in that case, he wouldn’t have become the wildly popular figure that he was, and nobody would’ve cared what he was preaching. And yes, as I will discuss in my next post, there really is a troubling, dreadful element in Sartre’s view of freedom; whether he saw what it was, however, is questionable.

Lastly, both made the argument that one particular value (the individual’s life for Rand, freedom for Sartre) was the highest of values, since without it no other values are possible. Unless I’m missing something, both arguments commit the same fallacy of thinking that a necessary condition for the existence of values both (1) necessarily has value in itself, and (2) is of more fundamental value than any of the values that follow from it. (And yes, all of this is just a teeny bit caricatured. This isn't one of my serious posts. You probably guessed that from the title.)

So while I will go on reading Sartre, slipping him occasionally into papers, and having late-night debates about him over beer, while ignoring Rand and making fun of her followers, I just can’t help wondering if they were cast from a similar mold. All this, of course, pertains not so much to similarities in their philosophies, but similarities in what made them famous. But we can be a little more serious tomorrow...

As a disclaimer, let me point out that I think Sartre’s nifty. Also, reading Sartre was one of the factors that pushed me from being interested in philosophy to wanting to study it professionally (I know I shouldn’t admit things like this publicly, but in my defense: I was 16 at the time). And I still think that, in many ways, Being and Nothingness is a genuinely great work of philosophy: it was one of the very few major works that aimed not just at resolving abstract metaphysical problems, but very sharply followed that ancient dictum of philosophy: Know Thyself. Sartre’s account of self-deception and the numerous permutations of it worked out throughout the book serve me well to this day in analyzing both myself and other people.

My feelings for Ayn Rand are a bit less warm. I read The Fountainhead when I was 17 (in order to enter the essay contest) and tried to follow up by reading some of her theoretical work; fortunately, I’d already read enough real philosophy by then to find her pretty laughable. I still think The Fountainhead is, overall, a good novel despite being seriously undermined by the attempts to get a “message” across (though Sinclair Lewis’s Arrowsmith is a more realistic and overall superior attempt at something similar: for one thing, it’s peopled by real characters rather than thinly disguised social virtues and vices). But really, I pretty much think Rand is a joke. Sartre, on the other hand, isn’t. And his tireless political commitment, though occasionally misguided, is impressive. So, what’s the connection?

What they share, really, is a similar delusion, or perhaps a similar lie: that they are conveying an uncomfortable truth when, in fact, they are telling the people exactly what the people want to hear. Let’s look at Rand’s case. The harsh truths she tells her American audience go something like this: Capitalism is wonderful. The world is objectively real. The highest value is individuality. Individuality consists of never collaborating with others, as that would water down the uniqueness of this individuality. And, naturally, morality requires that we care only about our own happiness and self-interest. Yup, integrity means looking out for number one. Obviously this is earth-shattering stuff.

Sartre is a better writer (though he also has a tendency to undermine the plausibility and readability of his fiction by overly un-subtle philosophical messages), and a much better philosopher, but this is to be expected: the French public is simply more demanding of its intellectuals. But what seems a bit disingenuous are his remarks about the “dreadful burden” of our freedom. He is telling a public that has just emerged from an occupation (in which many were complicit), a public that no longer trusts the old values, that, hey, it’s ok: the old values are only right if you choose them. And you’ve got the power to break free. All you have to do is recognize it! Sure, Sartre was accused of corrupting the youth and preaching despair, and I suppose his philosophy would’ve been more troubling if he were not preaching to the choir. But in that case, he wouldn’t have become the wildly popular figure that he was, and nobody would’ve cared what he was preaching. And yes, as I will discuss in my next post, there really is a troubling, dreadful element in Sartre’s view of freedom; whether he saw what it was, however, is questionable.

Lastly, both made the argument that one particular value (the individual’s life for Rand, freedom for Sartre) was the highest of values, since without it no other values are possible. Unless I’m missing something, both arguments commit the same fallacy of thinking that a necessary condition for the existence of values both (1) necessarily has value in itself, and (2) is of more fundamental value than any of the values that follow from it. (And yes, all of this is just a teeny bit caricatured. This isn't one of my serious posts. You probably guessed that from the title.)

So while I will go on reading Sartre, slipping him occasionally into papers, and having late-night debates about him over beer, while ignoring Rand and making fun of her followers, I just can’t help wondering if they were cast from a similar mold. All this, of course, pertains not so much to similarities in their philosophies, but similarities in what made them famous. But we can be a little more serious tomorrow...

Perhaps they were both monsters in their own way?

ReplyDeleteThe "philosophy" of Rand was that of the love-less heart---completely devoid of any Wisdom whatsoever. No real questions were ever asked!

Her "objectivist realism" was the mirror opposite (but exactly the same) of the "social realism" enforced in both Nazi Germany and the communist countries---a form of BRUTOPIA in which everything that is distinctively human sooner or later gets crushed by the machinery of the state or what Lewis Mumford called the Invisible Megamachine.

Wow. Talk about clueless. "Not a serious post" doesn't begin to describe it.

ReplyDeleteRand's point was not the (obvious) fact that you have to be alive to value, it was that life is what generates the need for values. Life doesn't merely make values possible, it makes them necessary. For the first time in the history of philosophy she bridged the "is-ought gap" and gave morality an objective ground in the facts of reality. She presents her argument clearly and in detail in "The Virtue of Selfishness".

To compare Objectivism and Rand to Nazism or Communism in any way shape or form is grotesque. Rand fled the inhumanity and oppression of communism and unequivocally denounced Nazism. She was an uncompromising advocate of limited government and a passionate defender of the individual's right to be free from all forms of statism.

"Objectivism the Philosophy of Ayn Rand" by Leonard Peikoff and his "The Ominous Parallels" should clear up any confusion for anyone who is genuinely confused.

I wouldn't say that they're both monsters. And I doubt that Rand is really exactly the same or a mirror opposite (a mirror opposite can't be exactly the same) of communism. But a world of unlimited capitalist pursuit where everyone is morally obligated to look out for themselves first and foremost doesn't strike me as much better than communism in practice, and as infinitely worse than communism in theory.

ReplyDeleteNigel: You might notice that saying that life makes values necessary doesn't help. Sartre, of course, says the same thing about freedom (i.e., if we are free, then no values belong to us innately; thus, we must choose all our values). But what follows? Why does "X makes values necessary" imply that X itself is valuable or, more importantly, that X is valuable in itself? Can't we choose a value that is higher than life? Or, for that matter, can't we have a telos according to which the overcoming of life (for example, in order to reach the divine) is the greater value toward which life merely impels us?

As for the "is-ought" gap, my own view is that if anyone has given us a way to resolve it, it's Kant. How does Rand resolve the gap? By claiming that all living beings necessarily value their lives? This only begs the question--it may indeed be true that we all value our lives and our happiness, but it doesn't follow that we ought to value those things. The is-ought gap is firmly in place.

Roman,

ReplyDeleteI'll take Rand's individualistic, selfish, capitalist society where each individual's right to his life and liberty are inviolate, over communism's subjugation of the individual to the needs of the collective any day. In fact owning my own life and pursuing my own happiness (while respecting every other individual's right to the same) is the only way I care to live. I certainly don't want others, least of all the state, to look after me. Communism is every bit as brutal and oppressive in theory as it is in practice. There's nothing noble or benevolent about enslaving men to serve the needs of others. Communism's bloody legacy is a logical consequence of it's irrational and inhuman theory.

Re Rand's grounding of morality: The argument is not a simple deductive argument. In a sense Hume was right, you cannot get from an "is" to an "ought", from factual premises to a normative conclusion, purely deductively. However, Rand's argument is not deductive but inductive; it is firmly based on observation and on an inquiry into the nature of the concept of "value". Nor does Rand claim that all living entities necessarily value their lives, I think it's obvious that many individuals do not.

Her argument, which I can't do justice here, is contained in the essay "The Objectivist Ethics" in her book "The Virtue of Selfishness". If you want to refute her, refute that argument, not some out of context proposition.

Which brings me to a general observation... Rand's philosophy is derided by many philosophers (especially the analytic variety) for being simplistic, yet in my experience they are so blinded by their simplistic analytic method that are incapable of grasping some of her basic arguments, let alone her entire philosophy. IMO she is far more profound and rigorous than her detractors. Rand never indulged in contextless analysis of propositions, she always questioned the validity, origin, meaning and need of a concept. And it's that unique and precise epistemic method that enabled her to derive her morality from reality.

Rand's fundamentally inductive approach and teleological ethics makes a good contrast to Kant's method and his deontological ethics. You should give her a fair shot, you might be surprised.

Nigel:

ReplyDeleteIs a world where everyone looks out for themselves and has no obligation to others (except a purely negative one) a politically justifiable construct? Human beings enter society with a great range of inequalities, historical or natural. The default libertarian position, then, is that this is as it should be. The state exists only to maintain such inequalities. Can this be a morally justifiable position?

I think it cannot. The position is that nature (not to mention history) has made people a certain way. And this is, indeed, how things are. But if we ask the further question about how things ought to be, we cannot answer that question simply by pointing, once again, to how things are. That human beings have a wide range of very different abilities and advantages is an empirical truth; that persons (individually or collectively as a state) have no obligation to compensate for inequality--that, in fact, they are ethically bound not to--is not a moral claim at all, but rather the prudence of the priviledged.

Further--and this is precisely the thrust of the is-ought gap--inductive arguments can never tells us how we ought to act or what ought to be. They can tell us only, given how things are, how we can change (or not change) them in order to achieve a pre-given goal. But if we are to subject the goals to scrutiny, then either they are simply an expression of our contingent desires, or there must be an independant standard for them, i.e., a moral one.

This excludes moral norms from the sorts of things we can find through induction. Induction is fine for telling us how to be healthy, or how to get rich. But it would be odd if induction could tell us how to be moral.

As for "enslaving men to serve the needs of others," that is precisely the motto of capitalism--to exploit the natural and social inequalities of human beings for the gain of the priviledged or lucky few.

Capitalism (Rand's laissez-faire capitalism) fundamental principle is that each individual has the right to be free from physical coercion, so they can use their mind and act on their own judgment to pursue their happiness. Every other system demands the coercion of individuals to fulfill their "obligations" as deemed by the state, the Monarch, the Theocrat, the Proletariat, the what ever. Any such system is anti-reason, anti-life, inhuman and immoral. And every such system, from the Dark Ages through to Soviet Russia, Cuba and modern day Iran, result in oppression, misery and bloodshed.

ReplyDeleteI think Rand would say the goal of morality (on her view, life and happiness) is "pre-given" in the sense that you exist. If you want to remain in existence and live life to the full, then (a rational) morality will show you how to attain that goal. But whether you choose to value your life or not is up to you.

In closing my participation in this discussion, I leave you with a couple more references on Rand's ethics, should you choose to do a serious and philosophical study of her ideas:

"Viable Values - a study of life as the root and reward of morality"

"Ayn Rand's Ethics: The Virtuous Egoist"

Both are by Tara Smith.

"Every other system demands the coercion of individuals to fulfill their "obligations" as deemed by the state"

ReplyDeleteTwo things. First, a political system necessarily involves at least some coercion. Fortunately for us. Second, laissez-faire capitalism simply substitutes coercion by the most privileged for coercion by the state. Frankly, I'd rather be coerced by a system into which I have some input and the functions of which are at least partly transparent.

You could of course respond that the "privileged" are only so because of their own natural talents, which no one else has a right to profit from. The obvious rejoinders are that (1) being born with something does not make it rightfully yours, but only de facto yours, and (2) since these individuals can only profit from their talents and labors within a law-governed framework, it seems perfectly reasonable that they should also have obligations to others, without whom this framework could not exist. Otherwise, they would simply be parasites.

It is also not sufficient--or clear--to understand coercion merely as physical coercion. The state does not physically make you pay taxes, for example; it simply punishes you if you don't. Let's say you are born into a poor family, are unlucky enough to have no natural talents, and do not get the best education. And let's say that your choices, then, are to get a minimum-wage job with no job security or health care or to starve to death. Are you "coerced," in this situation? One could say "no, this is just natural; it's nobody's fault." But since you could not be in such a situation unless you happened to be born into a human society with a particular economic and political structure, that answer would be way too simplistic.

Obviously the governments you describe are not desirable ones. But to suggest that they are the only possible alternatives to laissez-faire capitalism seems odd given that there are plenty of functioning alternatives around--for example, there are no laissez-faire first-world countries in the world today, to my knowledge.

"Any such system is anti-reason, anti-life, inhuman and immoral"

These are just bits of rhetoric to throw around. Very pretty.

"If you want to remain in existence and live life to the full, then (a rational) morality will show you how to attain that goal. But whether you choose to value your life or not is up to you."

Whether you value your life may not be up to you (this is questionable), but whether or not you ought to value your life is a different issue. If your life is that of wasted-talent or, more to the point, self-service, then it may not be worth valuing. This is the difference between prudence and morality. The question of prudence is, "given that I value my life, what should I do?" The question of morality, on the other hand, is, "given that I am alive, what should I do to make my life worth valuing?" That my life has worth to me is one thing; that my life actually has worth is another.

Rand pretty much just begs the question on this--for her, "x has worth" is equivalent to "x has worth to a particular individual." So she resolves the is-ought gap by pretending that there is no gap. This has the effect of blurring the distinction between what I ought to do and what I want to do.

Roman, you should probably have at least read something by Ayn Rand before making such a fool of yourself. Honestly, reading your post, I could only feel embarrassed for you.

ReplyDeleteThat's funny, that's exactly how I've always felt about Ayn Rand! I think most of her supporters might benefit from reading some philosophy, too.

ReplyDeleteI've written a piece comparing Sartre and Rand here (I like them both):

ReplyDeletehttp://praxeology.net/racism-ayn-sartre.doc

Rand's solution to the is-ought problem is to state, very slowly, that she is right. Let's see: "...let me stress that the fact that living entities exist and function necessitates the existence of values and of an ultimate value which for any given entity is its own life. Thus the validation of value judgements is to be achieved by reference to the facts of reality. The fact that a living entity IS, determines what it OUGHT to do."

ReplyDeleteSo if you have life, then you ought to value your life? Why? Because everyone values their own life? Because Rand herself values her life? What she is saying is that since (most) everyone values his life, everyone should value his life.

Rand's philosophy is illogical. Just because something is doesn't make it good; Rand commits the naturalistic fallacy. Furthermore her derivation actually goes AGAINST natural laws; specifically, evolution. We value our lives because it is in our genetic code. If organisms did not "value their lives," then they would not survive. So the only organisms which survive are those that value their lives. So where did this become ought? The only reason I can see would be: this is good because human life is good. Why is human life good? Because we value it. Do you see the circular reasoning?

As a side note- Rand seems to be quite the proponent of right-wing capitalism, going so far as to make self-contradictory claims to support it. I don't think this should detract from her philosophy- it was merely a product of being a Russian-born immigrant in the McCarthy era.

This is too much.

ReplyDeleteHaving read most works by both Sartre and Rand, they share many similarities though a few substantive differences.

ReplyDeleteI am an admirer of the works of both.

Somewhere in these posts the author hit upon what I believe is the only genuine flaw in Rand's philosophy: that the individual cannot or should not choos a value that is higher in value than their own life.

Whomever said that one of Rand's positions was that collaboration is bad has obviously not read ANY Rand.

To the mind of Roman Altshuler:

ReplyDeleteIf you cannot see the damned (I mean it, to the full extent of the word) stumbling contradictions in what you call "real philosophy," the fault is your own.

If your epistemology and metaphysics allows contradictions, abide by those laws - live in whichever way you want. However, before you accuse men of foolishness (or stupidity), be sure you know why.

The moral crime of replacing someone's judgement for your own (as I've realized every anti-Ayn Randian has done) is something you should realize as such.

The beauty of Ayn is that she (unlike you) did her research.

You read few of her work and claim to know that she is wrong? The teachers whom fed you the notion that such utter laziness was righteous and noble must have achieved such jobs by the same philosophy.

The very same teachers whom taught you the value of half-work and sloppy-research, I suppose, valued you greatly?

It does not matter.

You and the teachers, mystics, and witch doctors behind you - the whole of your "real philosophy" - it will not last.

It's lasted at least two and a half thousand years, so I'm not too worried. But thanks for your deep and obviously well-researched thoughts. Yes, it's true, Kant, Aristotle, McDowell, Korsgaard, and all those other people I'm reading are obviously mystics and witch doctors. Gosh, if only some free thinker could point this out to all of us!

ReplyDeleteBy the way, I'm sorry, this is Roman Altshuler's body writing. His mind is away at the moment, brewing up some eye of newt.

Why is it that every time a person wants to comment in favor of Ayn Rand the first thing that they point to is the fact that "you obviously have not read X because you have miss-stated X because X really means Y." It seems to me that Rand has constantly tries to blame everything on the philosopher. See the introduction to the Fountainhead were she remarks that the improper use of egoist is not the actual fault at the righter but rather the fault of the philosopher whom puts emphasis on these words. Ultimately, Rand fails to construct a coherent philosophy and often finds a scapegoat, ignores issues with her philosophy, and denies that society was formed because the individual is a failure, all in order to prove her point and this is a large part of why real philosopher's find fault in her arguments (objectivism ethics are moral relativism repackaged). Being a philosopher that is in a constant in search of the perfect moral system, I have declare that the Kantian Categorical Imperative and it maxims are the closest we can get to a perfect system because while it does leave room for the implication of the individual, it does argue that there are a set of rules that can not and should not be impeded.

ReplyDeleteRoman, you use very faulty logic when making this point:

ReplyDelete"It is also not sufficient--or clear--to understand coercion merely as physical coercion. The state does not physically make you pay taxes, for example; it simply punishes you if you don't. Let's say you are born into a poor family, are unlucky enough to have no natural talents, and do not get the best education. And let's say that your choices, then, are to get a minimum-wage job with no job security or health care or to starve to death. Are you "coerced," in this situation? One could say "no, this is just natural; it's nobody's fault." But since you could not be in such a situation unless you happened to be born into a human society with a particular economic and political structure, that answer would be way too simplistic."

Your fault is in trying to equate freedom from oppression with freedom from need. The freedom that Rand espouses and that a lazzes-faire society provides is freedom from oppression. Oppression occurs when a society takes freedom away from an individual.

When you give the example of a poor person with few skills and little education who is "coerced" into taking a low paying job with no benefits, this person is not oppressed by society, but rather by need. All people are oppressed by need, is the law of nature. People are "forced" to eat, drink water, and sleep in the sense that they will die if they do not do these things. This is not the same as oppression, in which another person or group of people forces an individual to do something.

You speak of some one "coerced" to accept a low paying job, but this is not, in fact, the case. This individual has the choices of taking the job or searching in nature for sustenance by hunting and gathering. You indict capitalism for limiting an individual's freedom, when it in fact provides more choices than nature does.

"Is a world where everyone looks out for themselves and has no obligation to others (except a purely negative one) a politically justifiable construct? Human beings enter society with a great range of inequalities, historical or natural. The default libertarian position, then, is that this is as it should be. The state exists only to maintain such inequalities. Can this be a morally justifiable position?"

ReplyDeleteThis is a misunderstanding. Every ma or woman has an obligation not impede on any other individual's freedom to act for their own happiness or personal gain. The cult of exploitation we see in our current western form of capitalism goes against Rand's philosophy; exploiting a worker means that the exploiter is taking away from that worker's ability to live a full and happy life. Also, the exploiter relies on the exploited party for their own personal gain, and therefore is not living as an individual, they are dependent on the one being exploited. This is against what Rand purports. There can be no coercion by the priveleged. This exploitation exists because of opposing moral ideas clashing.

Collaboration is encouraged, but only on equal terms, where two people each gain from the transaction, if there is no mutual benefit, the transaction need not occur. If one service is cheaper than another, and this is valuable to the person seeking the service, they are entirely free to use the alternative service. Nobody has been oppressed by the wants or needs of another.

"Nobody has been oppressed by the wants or needs of another."

ReplyDeleteWrong !

Extreme example - Hitler's wants and needs did oppress a lot of other people

Sometimes it helps to read a sentence in context before arguing with it, though.

ReplyDeleteGood distraction from my philosophy paper. As much as I do have a favorable disposition towards Rand it never ceases to amaze me how dogmatic and over-reactive their more adamant supporters are (though it happens with supporters/detractors of any philosopher, Rand and Marx especially). Maybe Aspergers is the next step in evolution?

ReplyDeleteThat was a fascinating read. I am extremely interested in the increased fascination with Ayn Rand in recent years.

ReplyDeleteI have not yet read any of her books in full but have read many excerpts.

I am in agreement with the poster immediately prior to me who is amazed by the dogma and over reaction of Rand's most adamant supporters. It is interesting to not that her most adamant detractor seems to be equally as over-reactive and dogmatic.

I wonder if the anonymous poster from October 24 is familiar with either Godwin's Law or the fallacy known as Reductio ad Hitlerum.

Thanks for the great blog and comments.

I found this thread accidentally, as Ayn Rand's philosophy seems to be referenced with a higher frequency in US commentaries (on the Web) since Obama's election.

ReplyDeleteIt is striking to me that no one uses behaviorism to understand Rand. She left Russia in 1923 (if that part of her biography is correct) after her family had to flee from the Bolsheviks. She must have been heartily disillusioned with the revolution she embraced at first.

Her defiance towards the state should be directly linked to the totalitarian drift of the USSR after Trotsky's exile. I'd like to remind everyone that the demise of the autocratic, Tsarist regime did not linearly precede Stalin's regime. There were quite a few years before Russia fell into totalitarism...

Rand's departure to the US, and her subsequent bout as Hollywood scenarist, certainly shaped her thoughts about individual power and the need for egoist freedom.

But this should not justify her disposal of individual "sacrifice" -by this I mean the individual contribution to the collective needs. Where does Ayn Rand say that some amount of personal "freedom" must be given up or dedicated to the global/overall well-being? Seems to me she ardently defends the opposite view- that NOTHING should be sacrificed to the Ego's will of power, as the realization of that tendency, freed of any moral barriers (obviously imposed by society as no imperative a la Kant), is THE condition which facilitates the individual's own imperative to happiness.

So that's something you can hear when Nazism/Stalinism are potent threats. But is this something relevant when Obama tries to provide minimal health coverage to all United States citizens?

Just some thoughts- haven't talked about Jean Paul at all here yet so let me just add that Sartre's engagement in social conflicts in the 60's concretized his will to change the way workers and society interacted. However, the communist back then (and to some extent still today) would not deviate sufficiently from the official party line to be credible. Most European countries are plagued with groups (unions, political parties, associations...) which still do not see the fundamental flaw of Stalinism (i.e. the efficient Communism) because they refer to other trends of the Russian (or French) revolution(s) as their founding principles. Sartre was no different as he idealized Communism without taking a hard look at the USSR, or at least justifying the absurdities by pointing to the constant aggression by capitalist societies (US, Britain, France...)

As a summary- individuals should be guaranteed a fair realm of freedom. This can only be done by society. Laissez-faire capitalism as it is today favors birth and rights over talent and competence. Ayn Rand, although candid and well-meaning, forgets the importance of sociological factors when considering individual trajectories.

Very interesting post. I'm going to start following your blog. I'm reading Atlas Shrugged at the moment, motivated by the knowledge that US leaders seem to allow Rand's thought to influence their decisions almost as much as the Bible. I typed in Rand vs. Sartre into Google, wondering if the two had anything to say about each other, as their philosophies do revolve around the individual.

ReplyDeleteI have to say, for a book celebrating rationality and self-interest as the basis of a moral society, there is surprisingly little rationality or accurate representation of reality in Atlas Shrugged. I should probably go through Rand's more technical descriptions of her philosophy, but something tells me it will be equally devoid of a foundation in reality, or even known scientific facts of the biology of altruism, political science, economics, or anything else.

Someone mentioned a bridging of the mythical "is-ought" gap. That's fine, but we have philosophers now doing that, and doing it using the physiology of human well-being as their starting point. I'm thinking of Sam Harris; I am trained in neuroscience, so I'm sure there are less "popular" thinkers doing this in academia, sorry for being so "mainstream." My point is that with the advance of scientific inquiry very clearly encroaching upon philosophy, I don't think there is much space left for poorly argued ideologies that seem to appeal to people for the mere fact that it is saying what people want to hear, and because of a media coverage that seems a little to "objective" (read: cowardly) to call BS on bad ideas. People arguing for Objectivism seem to do so by rhetorical means, not by referencing facts, but if someone is going to tell me how to live my life, they had better have good reasons. I haven't seen that from Rand supporters.