Wednesday, December 17, 2008

Friday, December 12, 2008

Inside/Outside CFP

Martin Shuster of Johns Hopkins asked me to post this conference CFP. Notice Terry Pinkard's name on there:

an interdisciplinary Graduate Student Conference

Monday, September 22, 2008

Short, Obvious Point

Labels: crass political observations

Wednesday, September 17, 2008

Am I Missing Something?

Is Intelligent Design a scientific hypothesis, even if a very unlikely one? Depends upon what we mean by 'scientific hypothesis'. But I think that the most plausible definition of science entails that it soooooo obviously isn't. That this point has not been commonly made makes me suspect I'm missing something.

On the one hand, any claim is 'scientific' insofar as it is supported by evidence. Any reasoning process is scientific insofar as it allows itself to guided by this evidence. The next question is, What counts as evidence? On a broad definition, ANYTHING can count as evidence. If I'm wondering whether or not to believe in God, for example, I might turn to St. Anselm, and to Alvin Plantinga, and to Michael Martin, and then Richard Dawkins, and then to the authority of my grandmother, who says that there's a God and I respect her opinion, to the fact that the Church has been around for a long time and this seems to be some evidence for Divine protection, to the fact that the universe seems largely explicable in purely physical terms and I favor Okham's razor, and so on and on. When I am forming my own personal beliefs, if I am rational about it, I will weigh all this evidence (never mind how I compare them for strengths and weaknesses), and form a subjective probability of belief. Let's call this the Bayesian Theory of Science.

The Bayesian Theory of Science is not a very good one--or at least, it's not a very sufficient one. Because on a more plausible definition of science, some types of evidence are going to be ruled out of court, and for good reasons. In addition to a commitment to evidence, and a commitment to allow one's reason be guided by evidence, the upshot of the scientific enlightenment was to stipulate that every state of the universe is fully explicable from the facts of an earlier state (actually, there's no need to temporalize this: any state of the universe U is explicable in terms of another state of the universe U'.) Maybe this wasn't such a stipulation. Kant made a good case in arguing that we simply had to think this way. But in any case, that is the idea.

By this definition, ID obviously is not scientific, even if there is some non-scientific evidence for a strictly Bayesian thinker to consider in its favor. The major premise behind ID theory is that the state of the Universe LIFE is inexplicable in terms of the state of the universe NO LIFE. Some non-universe actor intervened at some point, and an intelligent one at that. But what sort of claim is this? Clearly, it's a claim that a miracle happened. ID is a miracle-theory. Miracles don't belong in science, even if there is some non-scientific evidence to consider for their presence. I don't get why this point hasn't been made (that I've seen). When Spinoza and Hume and Hobbes were writing their long tracks against miracles, it wasn't just to prove that there were no miracles. More importantly, it was to convince their compatriots that the very notion of a miracle was incompatible with the emerging scientific world-view. We don't need to prove that science contradicts the possibility of miracles, only that miracles and any scientific theory are inconsistent.

Consider a situation where the scientific community actually adopted the ID position: what would be left to do? There would be consensus that it was pointless to research anymore how something like a living organism could arrive out of amino acids in the early conditions likely to have obtained on a primordial earth. In other words, they would stop trying to explain the origin of life. I would submit that any hypothesis, if true, that would halt scientific inquiry is, by definition, nonscientific.

Consider finally the argument Nagel is most famous for: the irreducible nature of subjective consciousness. There's good evidence in favor of this hypothesis. Anyone who is conscious has access to this evidence. The presence of this evidence is pretty overwhelming. Many smart people are convinced that this evidence is strong enough to ground the conclusion that consciousness is non-explicable in physical terms. But Nagel's own conclusion was not that consciousness has some queer, scientific status. His conclusion was there could not be a science of consciousness, at least not until our conceptual frameworks radically and unforseeably changed.

UPDATE: You might notice that two of the responses linked to above are moderately complementary of Nagel's argument. I would like to point out that both are Bayesians (or at least almost). Continue Reading...

Tuesday, September 16, 2008

The Drinking Fallacy

I would say that that I don't mean to quibble, but that would be false, because I precisely do mean to quibble.Will Wilkinson has weighed in against there being a drinking age at all.

Here's an example of his argumentation:"UCLA professor of public policy Mark Kleiman, an ex-advocate of age restrictions, told PBS that he came around to the no-limits position when he saw a billboard that said, 'If you're not 21, it's not Miller Time--yet.' Age limits make drinking a badge of adulthood and build in the minds of teens a romantic sense of the transgressive danger of alcohol. That's what so often leads to the abuse of alcohol as a ritual of release from the authority of parents. And that's what has the college presidents worried. They see it."

Smells like a fallacy of false cause. It might be true that restricting legal drinking to 21 lends a weird romanticism to the activity (really though, who knows), and the abuse of alcohol is indeed a problem, but the idea that kids abuse alcohol because it is romantic is specious inference based on some pretty sketchy folk sociology. What is probably true is that some aura of romanticism encourages some extra amount of drinking, but drinking abuse is undoubtedly caused by many other factors, very few of which have to do with any sort of aura, and that together dwarf this supposed romanticism effect. Kids drink because its fun. In part it's fun because it's rebellious, but its fun for an whole lot of other reasons as well (inebriation feels good, individuals feel more sociable, you're more likely to get laid, worries are easy to forget, it's a social activity with the all the benefits of group membership, for some people the stuff just tastes good, etc.)

Will goes on:"There's certainly evidence that if we got rid of age limits, teens would drink more. But drinking more is a drinking problem only in the minds of neoprohibitionists. In a 2003 survey 22% of American tenth graders said they'd had five or more consecutive drinks in the last 30 days. But in Denmark, where there's no legal minimum to drink (though you have to be 18 to buy), 60% of 15- and 16-year-olds said they'd thrown back five or more in a row within the last couple of fortnights. Maybe you think that's too much. But the European champion of heavy teen drinking ranks as the world's happiest country and scores third in the United Nation's 2007 ranking of child welfare. In the UN listing the U.S. came in 20th out of 21 wealthy countries."

Um, maybe Danes are so happy because they drink so much. But regardless, it's not unimportant that Denmark is a wealthy, relatively homogenous and very well educated nation. I've spent a fair amount of time in Denmark. There is a lot of conspicuous drunkenness. Drunkenness is a problem in Denmark, as most Danes would admit on those occasions when they're not drunk. But being wealthy, well-educated, and committed to a generous social welfare state, they can afford a level of alcoholism that there's very little reason to think that the United States could afford. We have here a fallacy of false analogy. In any case, I don't think I'm going out too far on a limb to again assert that, even if alcohol policy has some effect on metrics like happiness and child welfare, the effect is going to be very, very small, to the point where overall social happiness and child welfare are completely unrelated and so can't support any inference either way.

Will also suggests that drinking-age and drunk-driving traffic accidents may not be positively correlated. I don't know any of the research, and so won't comment on that angle.

But he continues:"Salt makes things taste better. If you eat too much, it can kill you. But we don't need laws regulating salt."

Again, false analogy, in this case so obvious that there's hardly need for comment. Crack makes you feel better too, but if you smoke too much, it can kill you. A-bombs give you a sense of security, but if you let one off, it can kill lots of people. Point is: just about everything has some sort of benefit, and just about anything can be dangerous. We need to decide which are too dangerous to allow to be legal. He concludes:"In an America without a minimum drinking age, we would shift our focus from demon rum and car crash statistics to creating an environment where parents are expected to supervise their children and alcohol would become for teens just another thing, like bicycles or swimming pools, that can either make your day or take your life."

I'm pretty sure that this is perfectly fine anyway in most states. If parents want to ease their kid into a responsible drinking habits starting at an early age, I'm rather certain that there's no legal obstacle to this, and that even if there were, no one bothers to enforce it. I've at least never heard of a 15 year-old kid get into trouble with the law for enjoying a glass of red wine with his parents. Final point: kids drink and party too much for the same reason many have sex too early and too often: it's fun, and there's not much that legislation either way is going to affect that fact.

Personally, I'm agnostic on the issue. I do remember what a bummer it was not being able to drink legally as a 19 year old in college. But I drank anyway, and if it had been legal, that wouldn't have been different. Point being: the two are not all that related. I'm sure that arguments for Will's position are out there, but they need to be on principled grounds, not on utility effects. The arguments ought to be of the sort: 18 year olds should be able to legally drink, period, and if that entails some net costs, such is the price of freedom. We allow them to join the military. We allow them to vote. We allow them to have children and to marry. It seems a little arbitrary to prohibit them from drinking. If we are not going to argue the issue on these grounds, then if someone is goint to persuade me that lowering the drinking age would be better, they'd have to convince me that there's not after all anything wrong with the following inference: we will lower alcoholism among kids by making it easier for them to get it. That said, the arguments I've made suggest that there would be little effect either way if the drinking age were lowered. This is why I remain agnostic on the issue--I don't think it matters all that much.

Sunday, September 14, 2008

Torture and Americans

Here's Andrew's diagnosis:

"The idea that torture is immoral in itself seems alien to a majority of the millions who lined up to see Mel Gibson's The Passion Of The Christ."And again:

"This is what America now is: a country with the moral values of countries that routinely torture and abuse prisoners, like Egypt and Iran."Now take at a look at the groups listed with the United States: Egypt, Iran, Russia and Azerbaijan: all four are corrupt autocracies that are highly more likely to be torturing their own citizens than foreign nationals who happen to get swept up in a drag-net half-way around the world. In each of these countries an elite coalition not representative of the nation as a whole rules through an exclusionary and often precarious power-sharing agreement in which each member would happily game it to their total advantage if possible. This leads to a suspicious citizenry, wary of the state but perhaps more importantly, of other groups of citizens and non-state actors. In each case the state positively encourages this paranoia, knowing that the best way to deflect attention from itself is to play up fears of non-state groups.

Andrew's theory is that Americans have given up on a moral principle against torture. Many Americans no longer believe that torture is an absolute moral wrong. Torture is a conditional evil--'When a comparable moral evil is not at stake, torture is wrong'--whereby a negation of the antecedent entails a negation of the consequent. Andrew believes that this is a morally culpable error in moral judgment, confusing a categorical for a hypothetical injunction.

The trouble with Andrew's analysis (he has been one of the most forceful and effective critics of America's current torture policy) is that he has never given a solid argument for why torture is an absolute moral evil, and as Nagel and Bernard Williams have often pointed out, we have just as strong intuitions against moral absolutism as we do in favor of it, and there are certain moral dilemmas in which, no matter what we do, we will understand that we have violated one or the other of a fundamental moral principle. Let me propose, perhaps with much charity, that those American's in favor of torture understand it to be a true moral dilemma, as defined by Nagel, in which however one acts,

"it is possible to feel that one has acted for reasons insufficient to justify violation of the opposing principle...Given the limitations on human action, it is naive to suppose that there is a solution to every moral problem with which the world can face us. We have always known that the world is a bad place. It appears that it may be an evil place as well."*Those Americans in favor of torture maybe recognize that it is--to use another Nagelian phrase--a 'moral blind alley.'

Now, also take a look at those countries most opposed to torture as a means of state policy. They are Spain, France, Britain and Mexico. All have had bad and recent histories on the subject of torture, as both victims (Spain, Mexico) and perpetrators (France, Britain). They are acutely aware of the moral, political and cultural corruption that a torturing regime can effect. They are strongly against the policy because they are very sensitive to the dangers. The net effect of this history is a wary and distrustful view of the governmental security apparatus and policy.

It seems to me that this is what the many American's lack, not a moral principle. Americans in favor of torture as an official policy have not necessarily abandoned a moral absolute (if Nagel's right, it may not be an absolute in any case), but believe that this absolute has, after all, some conditions in extremis, and that the government can be trusted to respect those conditions. In other words, Americans are too ready to believe that the accused are actually guilty, and that that the accused actually have actionable information that they are withholding out of dogmatic hatred and an evil ideology, and that this information may save millions of lives. They have been persuaded of the falsehoods that ticking-time-bomb scenarios actually occur, and that other means of interrogation are less effective than torture. They believe that their government would only use torture in cases of imminent, deadly threats against real bad guys, rather than for any political or strategic reasons. All of these, as I say, are false and/or confused, but IF you believe all these things, then you have not necessarily abandoned a fundamental moral principle in supporting torture.

In other words, contra Andrew's interpretation, our values may after all be the same as those of Spain, France, Germany and Mexico, while quite different from those of Iran, Egypt, Russia and Azerbaijan; the relative variable here might not be moral value, but political judgment and trust of governmental authority. If so, then it's not that Americans have lost sight of a fundamental moral principle, they have lost sight of a political one.

*Thomas Nagel. "War and Massacre" in Mortal Questions. p73.

Constellations

Perhaps constellations are just heaps, then? This isn't quite the point either, however. Heaps may not have any internal organization or principle, but they are, after all heaps, regardless of whether I happen to be observing one or not. Heaps are not observer-relative or observer dependent, in a way that constellations, we should admit, are. If the earth were in a different location in the galaxy, our night sky would appear differently, and there would be different constellations for us.

Easwaran concludes that

"rather than being composed of stars (as in the actual glowing balls of gas), a constellation is composed of beams of light reaching Earth."I doubt that this is right. If this were right, we could equally say a traffic light isn't really composed of metal and circuitry, but of photons. The difference between something really being something, and something's being instead the media by which information is transmitted does not cut the difference between real unities, heaps and observer-dependent heaps. This observation is one of the motivations behind the causal theory of perception: the content of a perception is whatever object is responsible for eliciting that perception, regardless of how it did so (through light-beams, through wireless transmission to the chip in my brain, etc...). (There are problems with the causal theory of perception, obviously, but making this point is one of its merits). Certainly those the stars in a constellation are partly responsible for my perception of the constellation, and so must be partially included in the content of that perception. Of course, there's nothing special about stars for constellations: if galaxies were bright enough, they could be parts of constellations, and I think I'm right that some constellations include nebulae as members. The point is not that stars must be part of the definition of constellation, but that a constellation must contain some reference to the objects responsible for the light that reaches me, regardless of what sorts of objects those are (they could even be disco balls, for that matter).

Anyway, my point is not to critique Easwaran's account, but to echo his initial point, namely, that there is something a bit strange about objects like constellations. So, while I don't think that he's right to say that 'constellation' has light-beams as its reference, he correct to note that angles of sight are not incidental to the meaning of 'constellation': constellations are observer-dependent objects; they do not exist without observers, and the proper concept 'constellation' must include that somehow. However, it is ALSO not the case, I'd say, that the term' constellation' refers to a mere appearance (even an 'objective' one--in the sense that the appearance of a stick being broken in the water is an objective fact about the way that stick will appear to an observer, even though it is not any property of the stick or the water or any other such object), any more than it the case that, when I think 'unicorn' I'm referring to my idea of a unicorn.

So, Easwaran's right, constellations are queer sorts of objects, and it doesn't take a lot of reflection to convince yourself that lots of regular objects (maybe all middle-sized dry goods) are queer in this sort of way. But putting that to the side, here are some other examples of objects that, given what I've described, are queer in the same way that constellations are queer: they are observer-dependent objects, but are not mere appearances.

Horizons, rainbows, colors, mirages, the 'man in the moon,' maybe all paintings and images....

Anyone have further examples to add to the list?

A further point: Daniel Dennett is a fan of the 'grand illusion' theory of conscious experience. We take in limited information, and then our brains construct the filling material that makes it seem as if we have rich, robust experiences reflecting a rich, robust external world. That' s an interesting response to an interesting theory, but it hardly exhausts the interest in these matters. I mean, presumably, when light refracts through water droplets and then reaches my eyes, my brain sometimes runs the rainbow function producing the experience of a rainbow, but even if my brain does create these illusions, that doesn't answer the questions above, because those illusions are still 'objective,' in the same way as a constellation is.

Machiavellianism

An interesting if obvious observation from this week's New Yorker book review:

Continue Reading..."There is today an entire school of political philosophers who see Machiavelli as an intellectual freedom fighter, a transmitter of models of liberty from the ancient to the modern world. Yet what is most astonishing about our age is not the experts’ desire to correct our view of a maligned historical figure but what we have made of that figure in his most titillatingly debased form. “The Mafia Manager: A Guide to the Corporate Machiavelli”; “The Princessa: Machiavelli for Women”; and the deliciously titled “What Would Machiavelli Do? The Ends Justify the Meanness” represent just a fraction of a contemporary, best-selling literary genre. Machiavelli may not have been, in fact, a Machiavellian. But in American business and social circles he has come to stand for the principle that winning—no matter how—is all. And for this alone, for the first time in history, he is a cultural hero."

Monday, September 8, 2008

Beyond Belief

Does it make sense to ask, Is this accurate? I don't think so, for a reason I'll provide in a moment. But even if I do not think that this sort of work is something that can be accurate or inaccurate, it is still possible to disagree with certain claims made in it. I have one claim in particular in mind that I'll address below, which is this: that the difference between ourselves and our ancestors has less to do with different beliefs, and more to do with different 'experiences.'

First let me register my qualifications on philosophical historiography. Taylor tells a story about how, roughly five-hundred years ago, a porous experience of self was supplanted by a buffered experience of self. As Taylor acknowledges, this account has similarities to Weber's theory of Entzauberung. For us, purposes, meanings, intentions, and values are intrinsically mental predicates, whereas for those who experienced a porous self, such things were parts of the environment as much as parts of the soul, and a world that itself embodies meaning, purpose and value is a an enchanted, zauberische world. Of course, while I detect a hint of nostalgia in Taylor's piece (he is a practicing Catholic after all), Taylor's work succeeds as admirably as any at being a fair-minded, work of descriptive philosophical historiography.

Taylor’s story is consistent with itself. We might even be able to say that it is consistent with the facts, were it not the case that in history, more often than not, the facts are decided by story we are trying to tell. Danto made this point classically: we can say, in a rather uninteresting but unassailable way, that at 7pm, just after sunset, January, in the year 49b, Julius Ceaser rode his horse across the river Rubicon--but this hardly makes for a historical fact. There is no history here at all. History requires tying earlier events to later events within a narrative framework, and that narrative framework requires ascribing psychological predicates like desires and intentions. Thus, to make the above fact interesting, we could say that Ceaser crossed the Rubicon and thereby ended the Roman republic--but this fact is unaccessible, or even meaningless, outside of the narrative about the fall of the republic and the rise of the empire. If that's the case, then I'm not sure what it would mean to call a work of philosophical historiography 'accurate.'

Nonetheless, there is one claim made in Taylor's post that is questionable regardless of whether it is accurate. He asserts that the difference between ourselves and the selves of our forebearers is not a matter of belief, but of 'experience.' He doesn't define experience, but I suspect he means something like existential mood, horizon, attunment, or what-not.

So, Taylor claims that beliefs are not at stake here. I wonder. Here is an example common both to our forebearers and many today: Heaven is a place beyond time and in heaven we will meet and enjoy company with our relatives and loved ones. 'Meet' and 'enjoy' are temporally extended predicates. It is not clear at all what it would mean to meet, or to enjoy oneself, divested of extension in time. This conjunctive belief cannot be maintained. It would not be right, in the end, to say that the belief is false; it would be better to say that it is confused. Nonetheless, it is a belief, at least in the sense that it is a proposition that, when uttered or written, a large number of people throughout history have and would assent to.

So, I want to say that while the difference between us and our ancestors is not a question of truth or falsity (ignorance vs. knowledge), it is a still question of belief; a question of whether a belief embodies a coherent concept. While it would be wrong to call our forebearers ignorant, it would be okay, I’d argue, to call them confused. Following this argument, while it is not fair to assert that our ancestors were wrong and we are right, it does make sense—I might claim—to say that we are less confused than they were, that we do not have here a mere difference in worldviews, but a normatively constrained difference wherein confusion and consistency are criterial.

As I said, I do not say that Taylor is wrong, only that his claim is questionable. I suspect that there really is something to the notion of 'experience' as Taylor uses it, but it is something that has to thought-through, not just asserted.

Labels: history, mind, phenomenology, Post-Modernism, psychology

Sunday, August 31, 2008

Consequence Argument Redux

Thursday, August 28, 2008

War (Cont'd)

When does a state of war exist among states? Earlier I started posting on this topic, but then got side-tracked by my own lack of focus. I began that post by noting that, while there is a easy answer to this question—two states are at war whenever the relevant sovereign powers have officially declared war to exist—but being so easy, it is also uninteresting.

I am interested in a plausible definition of war, and this requires some theory about what war is. This is complicated by the fact—I think—that two (or more) states can be at war without acutal, on the ground (or in the air) hostilities having actually broken out. England and France were at war with Germany starting in 1939, but there was no actual fighting for seven months. In fact, until the era of rapid mobilization, this state of war without occurrent hostitilies was quite common. Alternatively, hostilities may obtain between countries even while they are not at war (U.S.-Iranian relations in the 1980’s and 1990’s as a possible example).

My first idea was to borrow some concepts from Habermas, and to model states of war and peace off of his concepts of communicative and strategic discourse. To be at war is for only strategic relations to obtain among states, regardless of whether or not actual hostilities are present. One is at war, that is to say, when one has recognized the other state as an enemy—an enemy being a foe towards whom all attempts at mutual understanding and cooperation have been renounced, and only strategic interaction acknowledged. This theory relies upon the appropriateness of the analogy between communicative discourse aimed at understanding and diplomacy, on the one hand, and strategic discourse aimed at manipulation and war on the other. I think that there is something to this. Diplomacy, at its best, does seek to establish a common set of principles both (or more) countries accept as normatively binding. But the problem with this is probably obvious: much if not most diplomacy is not oriented towards achieving understanding, but instead operates according to precisely the sort of manipulation Habermas cites as characteristic of strategic discourse. Strategic discourse is manipulative, it should be noted, but it need not be deceptive. Strategic discourse distinguishes itself from communicative discourse in that it does not rely upon the mutual acceptance of norms. The gun-to-the-head scenario is a classic example: with a gun to your head, I can get you to admit that you love Bono, but not because you find the Bono-loving norm rationally binding. It’s just that you would prefer to make that foolish declaration over being shot. Strategic dicourse is governed by a utility calculus, and typically, even if it is deceptive, this is only because in general most strategic interaction involve situations of imperfect information (both as to facts and to intentions) with both sides trying to game the other.

This coda, however, is not fatal to the analogy. We could define war as that situation existing among states where all intention towards communicative understanding has been forsworn, and only strategic calculations figure. But again, there is a problem. For one thing, it is the fundamental thesis of Realpolitik that this is precisely the situation obtaining among states at all times, both in peace and in war. Realpolitik could even be defined as the theory that only stragetic relations obtain among states. Therefore, Realpolitik and this theory of war are inconsistent with one another, and one or the other would have to abandoned. There’s nothing absurdly wrong with this, but I’d prefer a definition of war that is neutral among competing foreign policy frameworks.

So let’s add this addendum: two states are at war when all communicative understanding has been forsworn, only strategic calculations figure, and physical hostilties are either threatened or actual. According to this definition, the Vietnam War was, in fact, a war, but so was the Phoney War (because hostilities, while not actual, were threatened). Anyway, I'm not completely satisfied with this definition, but it's good enough for now.

Wednesday, August 27, 2008

Is Zizek Really a Communist?

Zizek—I think—claims to be a communist. Not a party communist, of course, nor even a political communist, but a revolutionary communist. He would like us to place communism within the enlightenment tradition—not the namby-pamby enlightenment tradition of Mandeville, Mill or Rorty, but the bare-knuckled, paroxysmal enlightenment of the French Revolution. Enlightenment as revoution, sure, but revolution in the name of Objective Reason.

Zizek has made a highly entertaining career ridiculing lefty wimps, which could be defined as those who refuse—or better, verdrängen—the violent Kern constitutive both of human society writ large and the human psyche writ small.

In the end, Zizek’s standing as a revolutionary communist rests upon what is perhaps the one commitment that he is clear and consistent about: that history is driven by class struggle, and that class struggle is the only true opposition that is not a displacement or symptom of something else. He embraces the Althusserian paradox: everything is symbolic, but in the end, economics in terms of the class struggle is everything.

I could find many more passages like the following to support this claim:

“Class antagonism, unlike racial difference and conflict, is absolutely inherent to and constitutive of the social field; Fascism displaces this essential antagonism.”(full article here)

Zizek’s communism therefore ultimately rests upon his conviction that class struggle is the only ‘essential antagonism.’ But class struggle figures in Zizek’s thought like trauma in Freud, and the ‘real’ in Lacan.

In keeping with this, his only really clear and consistent commitment, Zizek’s one constant and never-ironic target of attack is the myth and concept of organicism: the idea that somewhere, somehow, at some time and in some way, human individuals and human socieities can be whole. This is, in the langauge of psychoanalysis, the fundamental fantasy, the myth of egoic wholeness as opposed to subjective fracture—and at base, the source of human aggression (hence the struggle). Zizek’s Ideologiekritik could be interpreted, finally, as the attempt to work the acceptance of castration into the political domain, for however disparate and scatter-shot his many polemics seem to be, they all aim to undermine any stable ideological position through sarcastic and irreverent dialectics of parody, mockery and satire.

Perhaps, in my opinion, Zizek’s most interesting thesis—never really stated in any systematic manner, but iterated often throughout his works—is that what binds people together into communities, and equally what binds together an individual person's (fantasy of) identity, is enjoyment. People and peoples differ from one another, form cliques, likes and dislikes, committ violence and atrocity, not from any shared beliefs, or shared values, or shared culture/ethnicity/background—peoples are formed according to what they enjoy. Beliefs and values are in the end--if they are anything relevant to social grouping--just symbols of personal and social economies of enjoyment. You are different than me—why? Not because you believe that The Mummy was an entertaining film, but because you actually enjoyed it. I am not one of you—why? Not because you value suburbia over city, but because you actually enjoy your large house and your long drive-way and your Wendy’s. I'm not a republican--why? Not because of any particular beliefs I have about health-care policy or geo-political strategy, but because I can't begin to imagine what it would feel like to take sincere pleasure in patriotism and a large, waving flag. Jouissance as the ultimate social concept, the primitive that makes sense of all the rest. I am not being insincere when I say that this is possibly be a real scientific insight for the social sciences—even though it needs to be theoretically systematized in a way Zizek has never even begun to try.

But if Zizek’s hails the class struggle, it is within the Lacanian framework of castration and the real. And if he promotes himself as a Marxist, it is against the one notion that animates Marx from his early humanism to the days of Das Kapital: that the class struggle, and therefore social struggle, can be overcome. Nonsense, according to Zizek. The closure, the suture, can never be accomplished, the fantasy must be destroyed, alienation and violence are the consitutive core of human kind, the letter has killed the body—the cause is lost, essentially. And yet, says Zizek, we must fight, struggle, resist, pursue this desire tenaciously to the death—what does this make of Zizek? Obviously—he is no communist, he’s an anarchist.

Labels: politics, Post-Modernism

Monday, August 25, 2008

The Real Hard Problem (Cont'd)

Labels: Husserl, intentionality, mind, phenomenology

Friday, August 22, 2008

'War,' What is it Good for?

Of course, there is a simple answer to the question, which recognizes that ‘war’ is a performative concept, like marriage, such that it is both a necessary and sufficient conditions for two states to be at war iff the relevant sovereign powers have declared war on the other state. But this is not very philosophically interesting, and not very useful. There are times when we would still like to pose meaningfully the question, even if these conditions are not met, and vice versa (see the Vietnam ‘Conflict,’ on the one hand, and the phoney ‘war,’ on the other).

This is not just an interesting matter in historiography, but has important moral implications. Many people argue that war is such a morally dangerous state for nations to enter that it requires its own moral status and theory (‘just war’ theory—books are written on this, unlike, say, ‘just trade theory’). Many of those who make these sorts of argument go on to say that it is worth suffering some severe economic, political, physical and moral hardship just for the sake of not entering that state. For instance, we might recognize that state X poses real dangers to state Y, that state X is dictatorial, oppressive, violent, that its citizens suffer extraordinary hardship under the current regime, and we might believe that a war would be effective at deposing this leader and relieving the suffering of these people—but because war is an extreme moral evil, it is not worth taking this moral risk.

Now, if you agree with Clausewitz that ‘war is just politics by other means,’ this sort of position will seem either silly or itself quite evil. Take a moral principle of Singer’s: if it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral worth, then we ought, morally, to do it.” Following this principle, war might be the only morally correct response to situations such as posed above. Anti-war proponents of the sort mentioned would have to make an argument to the effect that war, is, in fact, a sacrifice of comparable (indeed, more so) moral worth, if war is to be avoided in the situtation described.

What is that argument? One might point to the fact that war is necessarily violent, but so is starvation and execution and ethnic cleansing. If it comes to comparing the plausible violent outcomes of the two courses of action, then we’ve already ceded our ground on war as having a particularly heinous moral property—violence is the morally heinous property, and whatever lessens that is the right course of action. Anyway, I actually starte this post with another thought in mind, but I’ll get to that in a later post, cuz I gotta run. It concerns whether there is in fact any useful definition of war besides the obvious performative.

The Real Hard Problem

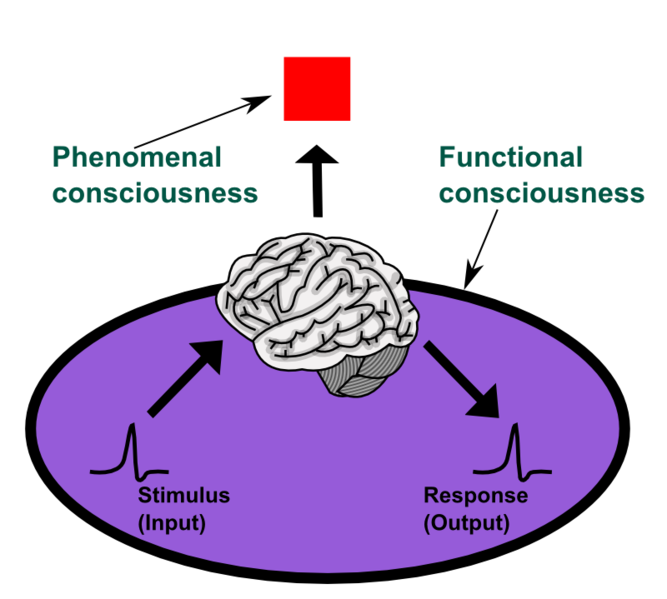

Chalmers opens The Conscious Mind (all citations below are to this edition) by insisting that two concepts of mind exhaust all there is to say about mindedness: these are the phenomenal and the psychological. The psychological concept of mind encompasses a broad definition of the field of cognitive psychology, and as such, is primarily oriented toward explainnig the behavior of minded organisms in terms of inner processes or mechanisms—such mechanisms might be striclty neurological, computational, connectionist, informatic or even Freudian (and by the way, don’t worry about meaning of ‘inner.). The phenomenal concept of mind Chalmers approvingly defines through Nagel’s ‘something that it is like to be that [minded] organism,’ a unique property I like to call ‘what-it’s-like-ity.’ Chalmers points out that this sort of property will only allow ostensive definition, and typically can be pointed out only through its association with publicly recognized psychological states. Because of this, there is is always a danger to conflate the pychological and the phenomenal, and while this is fine for most everyday contexts, in science and philosophy especially we must always be mindful of the distinction.

“…for philosophical purposes and in particular for the purposes of explanation, to conflate the two properties is fatal.” (23)

Minding this conflation, Chalmers famously argues, gives rise to a division of labor among philosophers of mind, whereby the psychological matters, while extraordinarily complex, are in principle solvable. In Chalmers words, psychological issues pose immense technical difficulties, but no real metaphysical ones (this claim I suspect is too cavalier, but I’ll not make anything of that here). But because the phenomenal character of consciousness fails to fit into any acceptable current scientific or philosophical framework (since dualism is ruled out of court), it is this feature that poses the truly ‘hard problem’ in philosophy of mind.

So, what then is this phenomenal property, exactly? Again, Chalmers doubts, at least within any existing conceptual repitoire, that anything other than an ostensive definition associated with recognized psychological states will be possible. He chooses pain as an exemplary case. A roughly acceptable definition of pain can be given in psychological (i.e. functional) terms, but this leaves out the phenomenal feature of pain that, in the end, makes pain matter so much to us. Pain is exemplaroy here in that this fact is common to all sorts of mental concepts, viz. a phenomenal property supervenes on a psychological one but does not seem to be essential to that psychological property qua psychological. One is tempted to say that this what-it’s-like-ity is a sort of sensation, except that it is that very feature whereby a sensation (like any other mental phenomena) becomes a sensation. At the very least, it seems to be a rather logically simple, discrete and ethereal property, one that is incidental to the psychological state underlying it (indeed, this is the whole rub).

Does intentionality fit into any of this? Chalmers is confident that intentionality (and therefore the theory of intentionality) belongs on the psychological side of the divide. Chalmers—typical of most of the anglophone literature on the matter—defines intentionality through the notion of a propositional attitude, and therefore accepts the semantic concept of intentionality. On this semantic conception, to be in an intentional state is to adopt a sort a sort of attitude towards a propositional-like structure (a belief, typically). And since it seems that a plausibly psychological notion of belief is available (something like: ‘a belief is a doxic attitude towards a state whereby one’s behavior would be appropriate in a situtation if that proposition were in fact true, and such that this state is normally brought about when that proposition is in fact true’), we can quibble about whether some phenomenal state is also essentially involved with intentional states, but it’s probably not worth the bother (see pp19-20).

This is where I would like to register my reservations. Chalmers wants to argue that the phenomenal and the psychological come together merely contingently, as a matter of empirical fact, but not essentially. This seems wrong to me. He can say things like this because he chooses phenomena like pain, or hearing middle-C, or the sensation of red, as his examples, but these sorts of ‘raw feel’ examples, and pain especially, are very untypical phenomenal states. For the most part, the world is revealed to us through our phenomenal states, and the separation between the phenomenal and the psychological that Chalmers insists upon is rather the exception than the rule. In other words, for humans at least, phenomenal states have the peculiarity of being intentional, ie., they reveal objects therefore are world-disclosing. Thus the phenomenal and the psychological come together, not as merely concurring phenomena, not as a mere matter of fact, but through some sort of necessity.

What is actually peculiar about the phenomenal feature of human consciousness is that it is intentional, which is to say, that it is by virtue of our phenomenal consciousness that we are aware of an objective world. Now, this introduces the heady problem of what to count as consciousness of an objective world, and therefore, of how to understand ‘objectivity,’, but this problem—I want to stress—is a formal or logical problem, and not primarily, maybe even not at all, a scientific one, and it is certainly not a problem that Chalmers has cared to recognize. Moreover, I believe that this is a legitimately hard problem, but unlike Chalmers own hard problem, we at least have some respectable ways to think through it.

I am arguing that, contra Chalmers, the psychological and the phenomenal are not together as a matter of mere empirical fact, but through a sort of logical necessity. When we speak about this essential unity of the psychological and the phenomenal, we are speaking about intentionality. In a follow-up post, I will say more about what this sort of logical necessity is (spoiler: it’s mereological), so I want to finish with just this observation. I do not doubt that as a matter of fact we will someday be able to construct complex systems that are genuinely psychological in the sense relevant to Chalmers. That is, we will construct systems that will, without speaking merely metaphorically, learn, memorize, process information, believe, perceive, and so on. And I also do not doubt that there are plenty such beings alive on earth already, viz., all the more complex mammals and fish and reptiles (I have my doubts about them amphibians). Nor do I doubt that animals have a phenomenal consciousness, again in Chalmers sense. But from the fact that we can both conceptually and in reality separate these two aspects does not in any way require that their concurrence in human consciousness is itself also merely factual or contingent. This would be like reasoning from the fact that, since some organic visual systems do not detect color, that color is merely incidental to normal human vision, a fact that merely supervenes upon visual psychology. But that’s not right. Normal human vision is intrinsically, not accidentally, colorful.

Labels: Husserl, mind, psychology

Tuesday, August 5, 2008

Phenomenology Revisited?

I’m all for the tone of this pep rally, but I might register some reservations about the message. Kelly suggests that the new (or renewed) interest in phenomenology among anglophone philosophers should thank in large part the pluralization of analytic philosophy itself. It’s as if analytic philosophy were sagging under its own weight, to the point where finally it’s either necessary or safe for anglophone thinkers to search out non-orthodox and non-canoncial sources in order to avoid theoretical suffocation. (For my part, I hope this isn’t just the result of a cohort of publishers all competing for some weird reason to get the ‘standard’ Husserl book out there.)

I’m not sure if that is right, but it sounds plausible (not that analytic philosophy has collapsed, but that the traditiontional project of analysis has—long ago—and that more recently it’s increasingly safe for ordinary philosophers to peruse a volume or two of Husserl, or even Heidegger).

But this version of things almost makes the return of phenomenology seem accidental, as if analytic philosophers simply grabbed for the nearest thing. At the very least, it neglects the fact that there were islands of phenomenology that survived the Great Deluge of post-structuralism and post-existentialism, populated with thinkers like Roderick Chisholm, Dagfinn Follesdal, Jaako Hintikka, Hubert Dreyfus and D. Smith himself. By the 1980’s, there was a dedicated group of Husserl and Merleau-Ponty scholars who were cris-crossing both fields and had the language and concepts ready for when interest finally did turn their way. (Lots of other thinkers I’m forgetting, but this is just a quick post—I’ll maybe update later).

In any case, instead of historiography, I’d like to focus on two issues raised by Kelly in the review, one positive, and one negative, both complementary. First, the negative. Kelly is among those who are impressed that analytic philosophers have finally discovered that we humans are minded, and not just linguistic, creatures. This is where the turn to phenomenology seems fortuitous. Anglophone philosophy has realized that subjective, first-person experience is an actual problem and issue, and then lo, here is a tradition nearly a century old with literally thousands and thousands of pages on the subject. A match is made.

But, if the renewed interest in phenomenology just comes down the fact that Husserl had gotten things like stereoscopic vision correct many decades before mainstream analytic philosophy, this is going to be a brief affair. To be sure, anyone would benefit from a good reading of Husserl’s analyses of internal time consciousness, but there are other reasons why phenomenology is interesting besides it’s field analyses. So, I’m taking issue with Kelly’s claim that

“the real contribution of Husserl's work is not systematic (though Husserl himself certainly had systematic ambitions); it lies rather in the careful and detailed analyses he provides of an enormous range of philosophical domains.”

If this is so, then I’m afraid that there is no real turn to phenomenology (or Husserl) in the first place. I mean, to discover something independently (say, that vision is stereoscopic, or that perception is inter-modal, or that subjective time is not in any easily determinate way a mere representation of objective time), to then discover that Husserl had some said something similar much earlier, and then to pat Husserl on the back for his prescience, is, while at least giving credit where credit is due, hardly a return to Husserl or phenomenology in general. (This is typically how these things have gone). At best, what this should suggest is that, if Husserl had gotten that right, then maybe he had other things right, and should be given a closer, second (or third, or nth) look. But I don’t see as much evidence of that happening. So, my negative point to make about Kelly’s review is his idea that phenomenology has much to contribute to contemporary philosophy of mind just because phenomenology was interested in first-person experience. This is unlikely. The danger here is that phenomenology simply becomes mis-identified as any careful scrutiny of experience from a first-person point of view, when, number one, it is not that, and number two, even if it were that is hardly its main point of interest. (And by the way, while this may be true to some extent for Husserl, how could Heidegger be read this way, as focused on first-person, subjective experience—isn’t Heidegger’s whole point to get away from this way of thinking about human being as mindedness as representations as subjective perception?)

Finally, Kelly is I’m afraid punching a bit of a straw man when it comes to analytic philosophy. As he would have it, analytic philosophy is simply the idea that all problems of philosophy are problems of langauge. But it is a bit unfair to put the idea that baldly; there was a keen insight there, which is that much of the time we simply are not clear on what exactly it is that we are asking, and by focusing on the way that we express our problems we can better focus of what is really at issue. Just as (among the giants at least) continental philosophy is rarely as disappointing as its caricature, the same is true of analytic philosophy.

But now to the positive point: Kelly does, in my estimation, correctly emphasize the unique role of description in the phenomeonlogical project, especially its uniquenes as method of inquiry to be distinguished from transcendental argumentation, deduction, empirical generalization, and so on. He does not emphasize this, but I want to. For instance, Kelly mentions that Husserl had, years before Searle, emphasized that even our run-of-the-mill perceptions of run-of-the-mill objects rely upon a ‘horizon’ or ‘background,’ a certain context. What are we to make of this horizon? Russell, as Kelly notes, had tried to make sense of it in terms of beliefs, but that is not adequate. I can see the barn façade as pointing to a backside even if I do not believe that there is a backside (Kelly’s example). Can it be explained in terms of ‘information,’ as defined by information theory? Or a set of background, pragmatic practices? Not sure, but in any case, what phenomenology at its best tries to uncover is the ‘true’ nature of experience prior to all theorizing or modelling. This may be a hopeless task, but it is the task on which phenomenology rests. It is the premise behind the descriptive method.

Finally, I would say that there is still something else important about phenomenology that Kelly does not get to. I would call the sort of ‘phenomenology’ that interests Kelly ‘phenomenology in the natural attitude.’ That is to say, he and others like him are doing phenomenology in the sense that they are striving for concepts and methods that will let us really and genuinely get at what it is like to have normal, quotidian experience. (As opposed to, say, sense-data theories that badly distort what everyday experience is like). This is a laudable and, I might venture, achievable goal. It is shared by thinkers like Alva Noë, Andy Clark and Shaun Gallagher. These thinkers are not interested per se in the epistemological projects that motivated, say, Husserl. But I think that this attitude can lend to a distortion of Husserl’s project as well. For instance, although he doesn’t put it in just this way, Kelly almost makes it seem as if Husserl’s method of reduction is intended to get at the precisely the field of experience that interests him, Kelly. But that is hardly correct. The reductions, obviously enough, have the express intention of getting the phenomenologist out of the natural attitude. And why? Because of the epistemological work Husserl hopes that opening up the phenomenological field will get right. That is to say, Husserl is not interested in just accurately describing everyday quotidian experience. He wants to understand how our knowledge about, say, arithmetic, arises out of this sort of experience. And this, for example, should be of interest to empiricists. If, for instance, what was really wrong with the early project of logical empiricism was not its logical or epistemological apparatus, but the combination and foundation of that apparatus upon a faulty and ‘phenomenologically’ inept concept of experience, perhaps a better, more sophisticated concept would save the intitial project. I think that John McDowell, for example, is doing something like this, and it just takes a brief moment of comparison to see how similar McDowell and Husserl are despite the fact that McDowell shows almost no interest in phenomenology per se (compare for example McDowell’s notion of propositionally contentful experience with Husserl’s categorial intuition.)

Alright, I’ve gone on enough, and I’m not sure that this is all coherent, but it’s my first impression on Kelly’s piece. Despite my criticisms, I really hope that Kelly’s optimism is warranted. We will find out I suspect sooner rather than later.

Labels: Husserl, mind, phenomenology

Tuesday, July 22, 2008

Agency, Endorsement, and Identity: A Case for Phenomenological Intervention

I often try—usually unsuccessfully—to push the idea that philosophy of action would benefit from a serious interaction with phenomenology. I tried to give an account of this to a well-known philosopher a few days ago but, partly because I was being overly exuberant and at the same time not entirely coherent, I got the distinct impression that he thought I was an idiot. Here I want to sketch out one place where I believe action theory needs phenomenology: on the issues of endorsement and identity. I am going to argue that a phenomenological account is needed to bring out the ways in which our agency is both creative and passive in such a way that acting on motives we do not rationally endorse may yet strengthen or at least express our agency.

In the latest incarnation of his theory of identification,

But I think

I think it leaves out a rather salient feature of our phenomenology, and this is the point at which phenomenological accounts are needed as correctives to overly rationalized or intellectualized views of agency. The feature is this: We sometimes find ourselves saddled with motives that we would not endorse, on deliberation, as good motives to act on. We might, in fact, reject them on every possible grounds, from their negative consequences in our means-end reasoning to their apparent undermining of our pursuits of the things we care about. But these motives might nevertheless come with, one might say, built-in endorsement. They appear to us as agency-defining for us, individually, as the persons we are. I might, for example, believe that all sorts of things are worth sacrificing some of my pride for. And if I deliberate seriously on the question, I might in the end decide that in some cases I ought to bite the bullet and overcome my pride. But faced with a concrete situation, I find that pride-based motives appear with a certain agential authority that I have not given them through any deliberation. While I may override these motives, either through impulsive action, or though further deliberation about the benefits of doing so, I find that these deliberations smack to me of rationalization.

There is a problem in cases like these. The mechanisms of practical deliberation normally taken to be agency-bestowing appear here as the exact opposite: from the first-person practical perspective, I am distanced from my deliberation, so that while I endorse all the premises in the deliberation, I still cannot help treating the process as a rationalization, undermining the agency-laden motives of pride. I might have every (good) reason to swallow my pride here, and yet I find that every such reason undermines my sense of my own identity and my own agency. The deliberate, rationally endorsed course of action comes up against a practical identity that I do not in any obvious sense endorse, but that I experience as somehow self-endorsing. (Think of John Proctor in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible bellowing, when asked why he will not sign his false confession, “Because it is my name!”)

The obvious existence of cases of this kind, I think, lends

My claim, in other words, is that we do not fully create our wills; we also discover ourselves to have de facto irrevisable wills. Because they are de facto irrevisable but in principle revisable, the phenomenology here comes into conflict with theories of agency that reject any passive component to agency, i.e., any component that we do not actively endorse and that we cannot reject without great harm to our practical identities. And this is also a case where, I think, the phenomenology has the upper hand: faced with self-endorsing agency-laden motives, I may well be aware that I could, in principle, withhold my endorsement of them; but this thought is only an abstraction, born of a self-deceptive view of the agent as a mind fully in control of itself. But at the same time, the motives we endorse and the self-endorsing motives we encounter usually work together more or less harmoniously. Agency is, one might say, a composite of what we are and what we make of ourselves. Phenomenology is in a unique position to study the functioning of this composite. Granted, it cannot exclude the problems of exhaustion-satisfaction or manipulation-satisfaction. But this shows only that phenomenology is not sufficient for an account of agency; not that it is not central to working out such an account.

Labels: action, phenomenology

Monday, July 21, 2008

Normativity and the Causal Theory of Action; Some Concerns About Causalism

Given the recent concerns by David Velleman and others about the “chilling effects” of blogging about conferences, I am a bit hesitant to say too much about the conference on “Normativity and the Causal Theory of Action.” But it was a superb and very interesting gathering, so I’d like to at least offer a few reflections. I don’t think I have anything to say that could even potentially be construed as negative, and if anyone from the conference objects, I would be happy to take down any of the points. In any case, this was a really impressive group of people, and many thanks go to Markus Schlosser, Bryony Pierce, and Finn Spicer for organizing it. The faculty and post-graduate students from

Interestingly, the conference did not really attain its initial goal, originally stated as being to bring together critics and supporters of the causal theory of action (CTA). It did not attain this for the simple reason that all five speakers accepted CTA, at least in some minimal form. Though some of us were a bit critical, no one argued against such theories altogether; the papers were more focused on attacking specific versions or formulations of CTA, or raising problems that causal theorists have yet to resolve, than attempting to throw CTA out altogether. Thus, Lynne Rudder Baker defended CTA, but struck a blow against any version on which actions are caused by neural events, providing a quite brilliant argument to the effect that action-causing mental states are constituted by, but irreducible to, their neural substrates. Matthias Haase questioned the extent to which CTA can account for rule following. Maria Alvarez provided a strong account of reasons as facts, attacking causalists for speaking of reasons as the causes of actions, as if reasons were reducible to mental states. And I (on a charitable reading of my paper) argued that CTA is only part of the story of action explanation; the other part has to be hashed out through agent-constituting narrative accounts, which specify exactly what it is, within the agent’s psychic economy, that rationalizes each action.

But while all of us were open to endorsing at least some version of CTA, Michael Bratman was the conference’s major defender of causalism. Having never seen him in action before, I must say that his reputation is well earned. He has the ability to get to the philosophical core of every paper, and thus his comments sometimes had an especially devastating tendency. In his own account, he raised three features central to human agency (planning, identification, and rational guidance), argued that these are fully compatible with CTA, and insisted that we need CTA for two major reasons: (1) If we accept that the actions of non-human animals are causally produced by features of their psyche, we need CTA in order to retain continuity between those animals and ourselves. (2) Accounting for the Davidsonian challenge of distinguishing between acting with a reason and acting for that reason—that is, we need a way of specifying the connection between an action and the motives for which the action was actually performed, as opposed to the motives the agent simply happened to have at the time of action, but did not act on. Bratman added to this the consideration that, if we are to be able to speak of acting for reason R, and acting for a different reason while thinking (perhaps through simple error, or self-deception) that we are acting for R, we need an account of what the right connection—acting for R—comes to; CTA gives us this.

Ultimately, though I find these considerations important, I am not fully convinced. Let us formulate two sorts of objections to CTA. Objections of the first sort argue that planning, identification, and rational guidance are incompatible with a causal account. Those objections, I think, are amply answered by Bratman, Velleman, Mele, Bishop, and others. But now take objections of the second sort, which might go like this: the features central to human agency are, e.g., planning, identification, and rational guidance. These features may well be compatible with a causal account of action. But these concepts themselves are not causal ones. Thus, the objection might go, although giving a complete account of agency need not rule out CTA, it need not appeal to it either, since the features central to agency are explicable apart from any reference to causal relations. I think we can answer the first of Bratman’s points: we can grant that there is no radical break between human and animal kinds of agency by accepting CTA as running in the background of any metaphysical account of action. But certainly we need not foreground CTA, especially since we can explicate the features central to human agency without constantly returning to the continuities between human and animal agential powers.

Thus it is really the second point—Davidson’s original one—that seems to require CTA. It rests on the question of whether we can give a coherent account of what it is to act for a reason (as opposed to merely acting with a reason) without appealing to causality. I’ll give here a brief, and all too incomplete suggestion: we had better be able to give such an account, since CTA requires it. The reason is this: saying that X caused Y isn’t very meaningful, unless we can give a further account of what that causal relation consists of. For example, we might say that the solubility of salt (together with the salt's being placed in water) causes it to dissolve in water, but this claim conveys little information apart from a detailed account of the dissociation of NaCl molecules in H2O. That account cannot, in turn, appeal to any causal claim, since it is supposed to make the causal claim meaningful in the first place. Similarly, if we are to explain sentences of the type “Agent S’s action A was caused by motives X, Y, Z”, we need to lay out what causation by these motives consists in, and we need to do this in non-causal terms. If (in Mele’s example) Al mowed his lawn in the morning because this was a convenient time to mow his lawn and not because he wanted to get back at his neighbor for waking him up early last week, then we need an account of the relation between his belief that this is a convenient time and his mowing the lawn, and an account of how this is different from the relation between his wanting to get back at his neighbor and his mowing the lawn. And these accounts seem to require talk of rationalization and the agent’s psychological economy that is not in turn dependent on any causal talk.

Labels: action, conferences

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

Educational Policy and the Extended Mind

On the other hand, it is undeniable that we are all a lot smarter than our counter-parts a hundred years ago. This is not only true in terms of literacy rates, basic mathematical competence, graduation rates and college attendance. Even our IQ’s have been improving (by what is known as the Flynn effect).

The first observation suggests that we really ought to be quite a bit less ambitious when it comes to public education policy, lest we waste a lot of resources and energy for negligible marginal benefits, incurring high opportunity costs. Prudent public education policy would replace the goal of making everyone smart (a pie-in-the-sky or ‘romantic’ view), and orient itself towards finding ways to make the incorrigibly dim nonetheless productive workers. On the other hand, the second observation suggests that there are in fact important and measurable returns to investment in public education—witness the fact that most Americans can now read, and know enough arithmetic at least to fill out their tax forms.

Let me call these respective positions ‘What’s the Point?’ (WTP) and ‘Yes We Can’ (SSP). WTP often responds to SSP in the following way: yes, certain metrics like literacy, basic mathematical competence, graduation rates, even a base-line IQ, have improved over the centuries, most notably the past one. But this achievement has been merely to allow the full exploitation of a natural capacity, and we are fast approaching the time when marginal returns on education investment fast diminish. In other words, whereas some prudent social policies have enabled increasing numbers of citizens to achieve their natural potential, we have not affected that natural potential itself, and once we reach it, there is not much more that policy will effect. Furthermore, for many students, we have already past whatever natural potential they have, and are now expecting results that simply are not achievable.

WTPers are fond of an analogy between innate mental capacities and innate physical capacities. Take running. Just about every human being can run, and some can run faster and farther than others. Surely some of that is due to training, diet, confidence, dedication--but in the end, a defnite limit is reached, and an innate distribution of ability becomes evident. Thus, (so the WTP argument runs) it is just as much folly to expect every child to learn calculus and to quote Shakespeare as it is to expect every child to run a 7 second 100m or a 4 minute mile.

But let’s consider this analogy a little further. Observe that ‘innate’ capacities, like running, operate within what are in effect artificial constraints. To measure one’s ‘innate’ running ability, we require (for example) that aids like drug enhancers, bionic legs, superhero lung transplants, roller skates, and so on, are verboten. But we do allow for scientific nutrition regiments, super-tech training aids, the use of all sorts of biometric technology. Without any of these artificial constraints, the relevance of ‘innate’ ability becomes not only specious, but moot. With superhero lungs and bionic legs, who knows, maybe I could run a one-minute mile. The point being, if we refuse to abide by artificial constraints, ‘innate ability’ becomes not only irrelevant, but almost incoherent. (Consider this question: what is the ‘innate’ life-span? If the physicalists are correct, and brain transplants become one day possible, and new bodies can be grown ‘brave new world’ style, then….you see the point).

I wonder why we shouldn’t consider ‘innate’ intelligence along the same lines. The equivalent of Olympic-criteria for measuring intellectual performance in the United States is the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Like the olympic sports, the NAEP sets up artificial constraints on the measurement of intelligence. The NAEP assesses skills in reading, math, science, writing, history, civics and geography. Verboten for students taking the NAEP are instruments like calculators, spell check, wikipedia, maps, and so on. But why do we insist on these constraints? It is hard to imagine very many scenarios where anyone in a ‘real life’ situation would not be able to avail themselves of any one of these technologies, so what is it exactly that we are measuring, and why?

The what is a very prickly issue, and innatists will get upset if you seem at all puzzled about it. But I think I can partially answer the ‘why’. We are still wed to a fundamentally Cartesian, fundamentally classical understanding of intelligence. According to this model, to ‘know’ something is to be a certain state, rather than to possess a certain ability. Thus, to ‘know’ that 98 + 113.5 = 211.5, or that the slope of a curve equals ∆x/∆y, is to have an intuitive insight into the nature of number, or in the nature of m. But consider for a moment: why is it that today, almost any decently educated 5th grader will be able to determine that 98 + 113.5 = 211.5, and any decently educated 8th grader will be able to solve for a slope-intercept? Before the development of a base-10 arabic numeral system, it would have been difficult for almost anyone to solve for the first, and before Descartes, to solve for the second. I am suggesting of course that there is a strict analogy between the use of a calculator and the use of a base-10 numeral system. Both are artifical, yet testers for the NAEP consider one’s ability to use the first still somehow ‘innate,’ while the latter is ‘artificial’—indeed, cheating. Why not then, instead of trying to measure some suspect ‘innate’ faculty, we instead measure ability—not under no constraints, but under constraints that are plausible and ‘realistic.’

Overall, then, I am suggesting that ‘innate’ intelligence no longer makes a whole lot of sense—although it still makes some sense, just like running—once we accept an externalist, “extended” theory of mind. In other words, we should take to heart the theory developed by Clark and Chalmers in their famous paper and apply it to the debate over innatism and educational policy. Returning now to the issue between WTP and SSP, we can at least partially explain the discrepancy noted at the beginning by recognizing that, because of technologies like a base-10 numeral system, even someone of ‘average’ intelligence can now solve for problems that, half a milennia ago, only the most educated and ‘innately’ intelligent could solve. That is to say, tests like the NAEP are in fact somewhat anachronistic, and I am sure that, if we did for instance allow for the use of graphing calculators, and the internet, that we would see marked improvements in test scores and therefore ‘average intelligence.’

Some caveats: this makes most sense when applied to mathematics, and to a lesser degree, skills like geography and history. That’s because the gains from technology (including symbol-systems) demostrably extend by orders of magnitude cognitive capacity. It’s not clear what role any such technology plays in writing and reading. I have some thoughts on this issue, but I’ll save them for the comment section if any one cares to explore the issue further.

Secondly, and less directly, I’m still not convinced that even on the innatists own ground and under their conditions that there is anything obvoiusly being measured. This is because I suspect that ‘innate’ ability, to whatever extent the concept makes sense, is influenced as much if not more by factors such as focus, attention, and motivation as by any raw capacity. The problem might be fitfully compared to the issue of indeterminacy. Whatever it is one is measuring by standardized tests, it will remain inscrutable whether performance results from raw capacity or from motivation, and so far, we have no reliable way (as far as I know) of controlling for one or the other. To see just how this issue informs the debate, check out this discussion.

Labels: politics, psychology