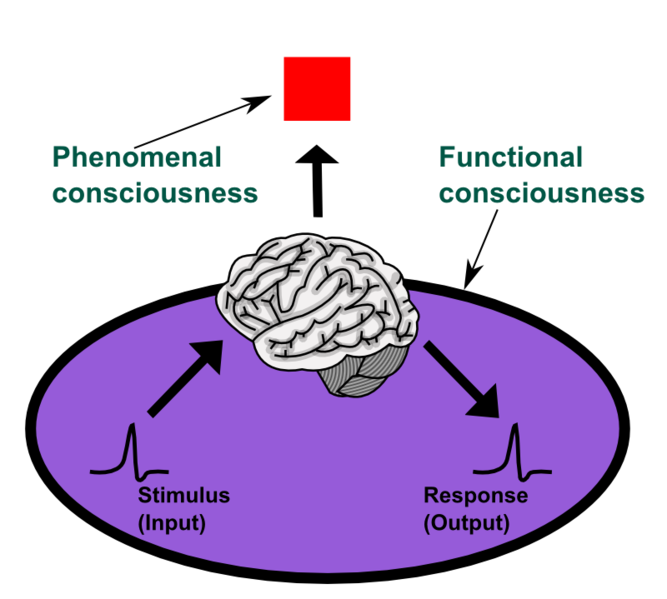

Chalmers' phenomenalism is of course very unlike the phenomenalisms characteristic of the early twentieth century. Traditional phenomenalisms focused upon phenomena as the objects or contents of conscious states (usually confusing or conflating the distinction). Chalmers’ notion of the phenomenal is closer to Brentano’s concept of inner consciousness than it is to these theories. Brentano characterized inner consciousness as a sort of second-order awareness that accompanies all conscious acts. Brentano’s inner consciousness—like, presumably, Chalmers phenomenal awareness—is necessarily second order in that is must always accompany an object-directed act (the act’s ‘primary content’). Presumably Chalmers (like Husserl) would disagree that all mental states are intentional, for not all mental states are object-directed or object-consciousness. But this should not affect the secondary status of phenomenal consciousness, so long as we admit that there is no such as ‘pure consciousness’ (mystics to the contrary). Chalmers, Brentano and Husserl would all agree—I think—that in order for phenomenal consciousness to arise, something else must be going on as well, whether that something else is object-directed or not.

However, from the fact that phenomenally conscious states need not be object-directed (intentional), it does not follow that object-directed states need not be phenomenal. Chalmers makes this unwarranted inference—and is not aytpical in so doing. He does so because, given different definitions of objectivity, there are different ways of accounting for intentionality (computationally, truth-semantically, informatically, etc), but the point is that none of these get at the fact that there are objects--and therefore a world--for us only insofar as we are conscious. This important blindspot has unfortunately eclipsed for many thinkers any true interest in (Husserlian) phenomenology, for lack of understanding the conceptual terrain in which it works. (NB: because of the ambiguities associated with the term phenomenal, I prefer to use the term ‘personal’: what is characteristic about human intentionality, as opposed to say either computer or dog intentionality, is that it is personal).

What is that terrain? Above I stated that in order for phenomenal consciousness to arise, something else must be going as well (although it need not be object-oriented, contrary to Brentano). Alternatively, as I just argued, in order for there to be object-oriented consciousness for persons, this consciousness must be phenomenal—or better, personal. Notice the modal terms: must be this, must be that. There is a necessity here. Contra Chalmers—as I noted in the last post—the co-occurrence of the phenomenal and psychological in the unity of personal consciousness is not a matter of mere empirical or contingent fact, but one of necessity. The question is, what sort?

Brentano observed that mental phenomena are characterized by a certain unity unlike that exhibited by physical phenomena. Mental phenomena—all the various contents of any given moment of consciousness—are unified internally, rather than externally; unlike the co-occurrence of physical phenomena, mental phenomena do not just happen to be next to each other (successive in Hume’s sense). This unity is supplied by the fact that all mental contents of a momentary act of consciousness are unified in one consciousness. The various contents and objects of a momentary act of consciousness (the 'specious present') don't just happen to be in the same 'place' in the way that the books and bed and desk I own just happen to be in this room with me now. The unity that underlies the contents of consciousness is tighter and more rigorous than the merely spatial co-location of items in my room. (This is of course an old point, going back at least to Kant, even Leibniz). Hume’s mistake, according to Brentano, was to believe that since there was no simple, detectable entity underlying the various presentations, there was no self. Mental phenomena do not appear to (in the dative) a self; the self is the unity of mental phenomena in one consciousness. Hume’s mistake was to confuse unity with simplicity, and Kant’s mistake was to confuse the appearance of external, material objects to a self with the presentation of a self’s own mental acts to itself (in a secondary, rather than dative manner, as discussed above).

We therefore need a way to talk about the unity of consciousness and mental phenomena—the unity of the phenomenal and the psychological in the personal—in a way that does not presuppose that his unity is a contingent matter of fact. That is to say, the unity involved here is of a logical or conceptual, rather than factual, sort. Brentano began the application of mereological concepts to the philosophy of mind, Husserl then formalized and extended this notion, putting it at the heart of his systematic phenomenology. When I claim, as I often have before, that phenomenology is a sort of formal science, it is this that I have in mind.

A final coda: What about the fact that many aspects and ‘contents’ of conscious life seem to go unnoticed, and in that sense, are impersonal? In other words, how do Brentano and Husserl avoid the imputation that their respective sciences are introspectionist (which, by the way, both deny)? Many have taken the results of phenomena such as change-blindness, attentional-blindness, blindsight, etc., to argue for the presence of non-conscious but nonetheless intentional contents of consciousness as a decisive refutation of the phenomenological method. While I won't go into details here, this attack is levied against a straw-man: neither Brentano nor Husserl have argued that the contents of mental phenomena were simply there waiting to be observed. Again, the argument relies upon the mereological theory of mind. Take the experience of a chord. As tone-stupid as they come, I could not begin to pull out the separate notes of any given chord. Are those separate notes present in my consciousness?

Dennett takes this as proof that there are no qualia, and therefore that only heterophenomenology will be able to describe the real contents of my consciousness. Brentano takes a different line: those notes are there, but as mereological parts of the whole chord as a phenomena of consciousness. They are there, because I hear the whole chord, but they are not explicit objects of my attentional consciousness. More importantly, the whole chord is there, not as a sum of those notes, but again, as the whole that is mereologically prior to those parts. Husserl’s own phenomenology departs precisely from here, and this notion of the whole that is prior to its part is precisely what Husserl means by ‘synthetic.’